Foundational Frameworks for Unlocking Elite Performance

I've spent the last 10+ years coaching elite performers - first as a technical and tactical coach (Division I football) and then as a performance psychologist in the NBA. I've had the privilege of working with head coaches, executives, physicians, and elite military units along the way.

Here's a science-backed look at the factors that I consider in my performance coaching across these high-stakes, high-pressure situations and some of the frameworks that I think allow the skills to cut across context.

Regardless of the performance environment you're in - whether you're saving lives, singing, or playing basketball - there's one common theme that sits at the heart of all performance coaching: elevating performance under pressure. That means I believe there's really one skill underlying every dimension of optimal performance: self-regulation.

The skills taught to the best performers in the world can help all of us learn to be our best when it matters most. Though these tools are most typically taught in the context of getting better at sports, they have a broad application for any of us looking to raise our typical performance and get the most out of ourselves.

First, let's unpack the types of performance.

Understanding the Performance: Typical vs. Maximal

Typical performance is how we function on a day-to-day basis. Maximal performance is how we handle the highest-impact, pressure-packed performances - it's the best we can do in a specific instance (Kaiser, 2019).

This framework is particularly helpful for figuring out what people mean when they're talking about the performance improvements they want. More often than not, what people are actually looking for is an elevated level of typical performance - to raise their baseline such that they're consistently getting better and doing more. With this understanding, good coaching matches the expertise of high performance with the expertise of the client, which allows for making meaningful progress quickly.

For CEOs, head coaches, physicians, lawyers, and other high-performance knowledge workers, typical performance tends to be the focus of performance coaching. While the moments of maximal performance matter, the reality is sustainable excellence and consistently performing well are much more important than one-off high-level deliveries.

What the research suggests is that, for typical performance, personality factors like conscientiousness, grit, and self-regulation, as well as motivational factors, like intrinsic and identified motivation, matter a lot. When I say personality factors, what I really mean is learned, repeatable patterns of behavior.

When it comes to maximal performance, skill and ability become a more significant factor (though at the very highest levels, skills and ability always matter).

This type of performance tends to matter more for the public performers we think of - people like Olympians and pro athletes who, in some cases, have one shot every four years to deliver the performance of a lifetime.

Of course, in an ideal world, you'd elevate both types of performance for all types of performers. Executives will sometimes need the skill to execute a one-time, clutch performance and elite athletes need high-level typical performance to get the most out of practice days.

Understanding typical vs. maximal performance allows you to filter down and figure out what skill might best apply to helping a high-performer reach their goal.

If you want to consistently be great, you have to want it and have a set of psychological skills that allows you to sustain it, and to develop those patterns over time. Those behaviors often include persisting in the face of adversity, experimenting and taking new risks, and staying grounded in your values.

In the case of typical performance, it's helpful to look to tools like values, goals, identity development, and techniques to change more enduring behavior patterns, like challenging core beliefs or teaching people how to manage difficult emotions.

In the case of maximal performance, some of those same tools might underlie how you prepare, but the reality is the performance demands themselves are different enough that they require skills like consciously increasing effort, narrowing the focus on a specific goal, challenge appraisals, and managing physiology at the moment.

The Core of Elevating Performance

I've written about what I see as the 5 main areas that all high performers must address to reach the top of their game.

At its core, I believe much of performance coaching involves moving each of these 5 skills up and to the right. And, the more I think about and refine my model, the more I think it's really about one factor moving most quickly in that direction, which allows the others to do the same.

Of the 5, data consistently suggests that self-regulation (Kaiser & Kaplan, 2006; Kaiser, 2019) is the key to high performance. The ability to control and direct your thinking, feeling, and behavior allows you to be a better teammate by shaping the way you interact. It facilitates leadership and discipline. It allows you to be thoughtful in your decision-making. It underlies effective executive function.

Self-regulation skills can allow you to thrive under pressure.

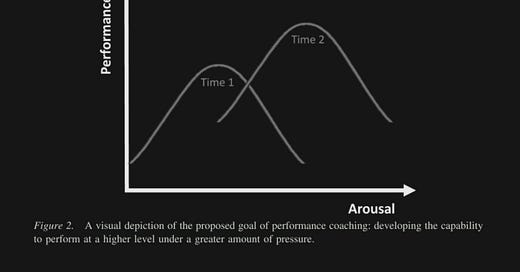

That means, to me, that most of the performance coaching - and the core of what it means for us to elevate both our typical and maximal performance - is about improving our ability to self-regulate. It looks like the graph below, where you see someone's improved ability to manage arousal (the most common performance limiter) allows for higher levels of peak performance over time.

The good news is that the skills we need to master ourselves and reach a higher peak are accessible to everyone.

"Excellence is an Inside Job"

I love this quote from Robert Kaiser in his 2019 article, Stargazing: Everyday lessons from coaching elite performers". It perfectly sums up what I believe, and what I think science is starting to confirm, separates the best from the rest.

Technical and tactical skills are prerequisites to greatness. The reality is that the things we espouse as most important - things like "scaffolding" and "growth mindset" - only really matter if you have mastered enough of the fundamental elements of the game you're playing, whether it's in the boardroom or on the court (no matter how hard I work at it, I'll never be an NBA player).

But, assuming you have the requisite skills, the rest of your performance is a function of the ways in which you train your mind and apply the mental skills you need to perform under pressure and rise to the occasion. It's about building your self-regulation.

Regardless of skill level, from amateur to elite, managing your mental is what allows you to raise your level of maximal performance and, as a result, change what's expected of a typical performance. The fundamental question of managing mindset boils down to: do I have the resources I need to succeed?

If the answer is yes, we get a cascade of physiological and psychological changes that tilt toward peak performance. We issue a challenge appraisal, and our brains and bodies are ready to spring into action.

If the answer is no, the opposite happens - our body starts to freeze up and it becomes harder to execute.

Much of the answer to this question depends on having enough mental skills training, and the requisite self-regulatory ability, to recognize what tool is required in that context and to know how to deploy it.

Building your toolkit

There's a suite of psychological skills that have been referred to as the "canon" (Anderson, 2009, p.11). These 5 skills are deployed by most performance coaches in some form to elevate performance under pressure and include relaxation (the ability to downregulate), self-talk, imagery, goal-setting, and concentration.

Arousal Regulation/Relaxation

When we think of peak performance and managing typical performance, the most common challenge people face is managing their level of arousal. We have to find a way to keep our energy in the optimal range and prevent it from debilitating us and breaking down our performance.

The main techniques for regulating our arousal are things we've explored together here, including mindfulness and breathwork, and things we haven't yet discussed, like progressive muscle relaxation.

Self-Talk

When it comes to our inner dialogue, I often liken self-talk to the "inner coach" (shout out to my colleague Amy Athey for the concept here) that we carry around with us. Unlike more traditional sport psychology approaches, I'm less interested in all your self-talk being "positive," and more focused on whether or not your self-talk helps you. I've also written about self-talk here.

When it comes to helpful self-talk, the goal is really to redirect attention to the performance task at hand. Eichinger (2018) uncovered the 3 forms of self-talk that tend to send us off the rails: thinking about something outside of performance, automatic negative thoughts tied to a core belief, and unresolved worries. These thoughts interrupt our working memory, one of the core executive functions we need to be our best when it matters most.

Our self-talk tools of choice include reframing, replacing, and defusing. Each of these allows us to either experience the self-talk differently or to lessen the impact of the self-talk overall. These techniques also enhance psychological distance, which Ethan Kross explores in his great book on the science behind self-talk, Chatter.

Imagery

The research on imagery is fascinating. We have some evidence that imagery alone can lead to some benefits in strength training, almost to the same extent as doing the work (this isn't a reason to skip the gym, but if you can't make it, perhaps 15 minutes of imagery is better than nothing).

The mind is a powerful vehicle.

Imagery has applications well beyond growing our muscles. People have built imagery protocols to heal physical injuries, develop new skills, and prepare effectively for peak performance.

The most popular model of imagery training is called PETTLEP. It involves incorporating 7 factors in your imagery practice to make it maximally effective:

In practice, my main use cases for imagery include preparation for a performance, refining the execution of a specific skill, and practicing anticipating and overcoming obstacles. Not only does imagery in these instances help an athlete plan effectively or improve their mind-body connection, it also builds confidence and helps implementation intentions feel more actionable. It's both pragmatic for performance and valuable for long-term development.

Goal-Setting

Goals create the context for any performance. Simply setting a goal is enough to guide our attention, and the result is often improved performance well above those who never take the time to set a goal for themselves. And, goals framed properly (typically, positively) can help us execute in the right way and tap into the benefits of a challenge appraisal (Renkema & Van Yperen, 2008).

Goals also allow us to focus our attention. If we can focus our goals and attention on what we can control (process goals), we can be more present. The more present we are, the better we tend to perform.

Concentration

Learning to concentrate allows us to stay tuned in to what's most conducive to high performance.

In addition to the previous four skills, mindfulness can be used to develop better concentration

skills. Mindfulness involves the repeated redirection of attention after a distraction back to the present moment. The more we can learn to stay concentrated on what we need to perform well, the better we can minimize distraction from the surrounding environment and anything internal that isn't helping us perform well.

Enjoy the ride

Getting better is supposed to be fun. Ultimately, all the practice and hard work, the fine-tuning of our skills and mindset, only matters if we apply ourselves to something we care about.

The more we learn about human motivation and well-being, the more we understand just how important it is to both make progress and notice the growth we experience as it happens. If you want to keep raising your game, you have to find ways to make the journey intrinsically rewarding.

References

Kaiser, R. B. (2019). Stargazing: Everyday lessons from coaching elite performers.