How to get 42% closer to the outcome you really want

Putting Goal-Setting to Work

Reading Time: 5 Minutes

What to Expect:

Scientific support for setting goals

Different types of goals you can set

Action steps to take right now

If you knew that all it took to improve your chances significantly was writing your objectives down, would you do it?

Few things improve your odds of success like setting effective goals.

From the mid-60s and into the 2000s, 2 scientists, Locke & Latham, set out to figure out exactly what helped people achieve success. What they discovered is that the simple act of setting goals - clearly naming and writing down an objective you’re working toward - was enough to tip the odds of success by a whopping 42%.

Goals work a bit like GPS. Most human behavior is guided by a goal, whether that goal is survival-oriented like securing food, or success-oriented like climbing the career ladder. The clearer we are about where we want to go, the easier it is to guide our behavior to the final destination.

Goal-Setting Basics

For goal setting to work, there are a few key principles we need to follow. And no, it’s not the SMART framework (that’s coming later).

Effective goals:

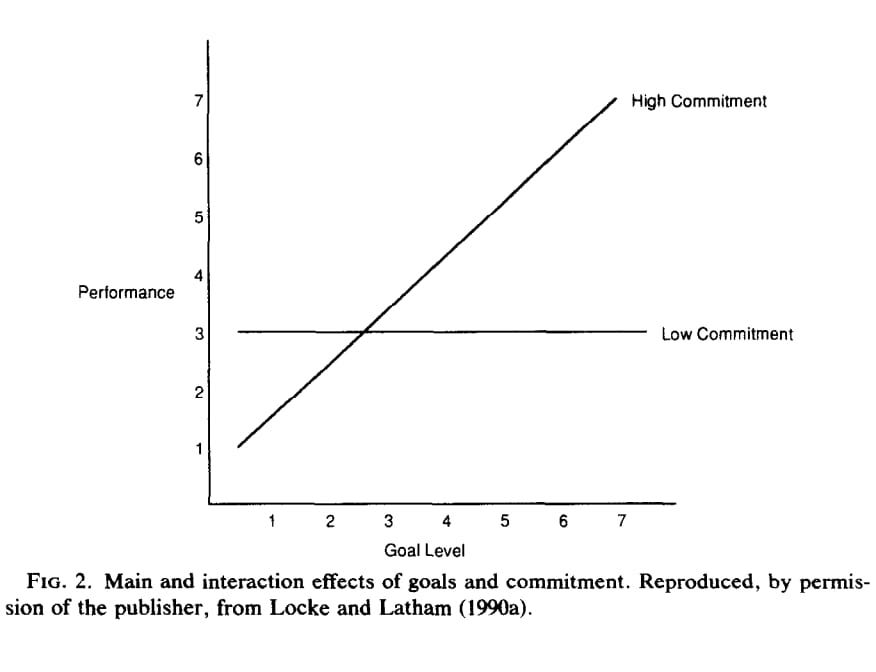

Are challenging. The higher and harder the goal, the more effort we’re likely to put in (assuming we believe we can reach the goal in our hearts, and success matters to us).

Spark commitment. Look, I don’t care who you are. If reaching the goal really doesn’t matter all that much to you, it doesn’t matter what goal you set. It won’t be super motivating. If, on the other hand, you really want to achieve something - your commitment is high - you’re likely to try harder and perform better. Good goals are framed around something that matters.

are self-set. Though we are often assigned goals from others at work, setting your own goals tends to be more motivating.

dial in on specifics. We have to have clarity on what we’re working toward and, perhaps more importantly, how we’ll measure progress.

A good goal should direct our attention, guide our energy expenditure (effort), and regulate how much we will persist toward achieving our desired outcome

How goals work:

They direct effort and attention toward goal-related activities, and away from unnecessary stuff.

They energize us, which increases our odds of performance and how creative we are willing to get on our way to our desired outcome.

Goals guide persistence. What we’re trying to achieve and the time we have to achieve it dictate how much we’ll push ourselves, assuming the goal matters.

Goals impact action. Once we have a goal, we start to use the strategies we currently know and develop new strategies to achieve our goal.

Here's a model of goal-setting and how it connects to high performance:

More on all this science soon. For now, let’s get to the setting of a goal itself.

Pick Your Goal Type

You’ve got 2 options here - non-specific (there’s no clear endpoint or objective target to hit) and specific (you’ve got a clear target you’re after). You can set a goal that is:

SMART (specific)

That means Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-Sensitive. There are about 500 variations of SMART (SMARTER, SMARTEST included), but for our purposes, the above framework will work just fine.

SMART goals are meant to be used in a very specific context - namely, when the 4 factors that make SMART goals most beneficial for performance are present. Those 4 factors are:

Ability: you’ve got the baseline level of skills needed to start working toward mastery (i.e, you’re not just getting started)

Commitment: this is a goal that matters to you and you’re willing to stick with

Feedback: you’ve got someone who can help you get better

Resources: you know how to get help when you need it

If you’ve got these 4 criteria, SMART goals can be incredibly effective. They can improve performance, help you achieve more, and create a sense of mastery. Without these 4, though, you run the risk of having the wrong goal in the wrong context, which can lead to anxiety and a sense of failure.

Open (non-specific)

Open goals are non-specific, vague ideas about what you’d like to accomplish. For example, you might just “see how far you can run in 10 minutes”. This kind of goal works well when you’re just starting out, and want to establish a baseline.

Basically, you just find one simple constraint (time, distance, etc.) and one simple goal that’s related to the skill you want to build (run, walk, read, etc.). Open goals tend to create a greater sense of joy and engagement, and often people are more likely to try a task again when they’re just starting out if they set an open goal.

As-well-as-possible (non-specific)

As-well-as-possible goals take the concept of the open goal and refine it one step further. These goals are best when you want to test your max. It’s kind of like “see how many reps of 225 you can do on bench press” at the NFL combine. If you want to really get a sense of your outer limits, as-well-as-possible goals are the way to go.

You can see why this works with the above example. If your SMART goal on bench is to do 25 reps, but you can really do 35 reps if you were doing as best as you can, your energy systems will regulate differently in the pursuit of each goal. The end result is you may feel more fatigued at 25 reps than you would if you were simply focusing on doing as well as you can.

Do-your-best (non-specific)

The final variation on open goals is to “do your best.” The difference here between a regular open goal and doing as well as possible is that you’re just asking people to give their best effort. They’re not after a specific metric (how far you can go) but rather a specific internal experience (max RPE, let’s say).

Though this nuance may seem unnecessary, the data suggests that these 3 non-specific goals do lead to different psychological outcomes. Specifically, do-your-best goals leads to greater mental effort; open goals, do-your-best-goals, and SMART goals all lead to higher RPE.

But perhaps the most important finding of all…

Regardless of what type of goal you set, your performance is better than setting no goal at all. And, some data suggests that up to 80% of people (!!!!) don’t set goals for themselves. Just picking one and getting started is enough to put you in the top 20%.

Action Steps

Forget New Years' Resolutions. Let’s focus on goal-setting that actually works.

Pick a single skill you want to develop, and then match that skill with the goal type above. Remember, if you’ve trained the skill some, SMART goals might be best. If you’re just getting started, pick a non-specific goal, and then figure out if you are trying to set a baseline, max out, or just see what you’re capable of.

Once you’ve worked toward the goal you’ve set, you can repeat the process and mix and match. For example, if you want to first set your baseline, you can set an open goal. After you do that, you can try a do-your-best. And, once you’ve done the skill enough, you can move on to SMART goals.

The key is to keep your goals top of mind and to focus on forward progress.

Bonus Step

As you work toward your goal, reflect on your progress. Reflection (the act of consciously thinking about how we are doing, what’s holding us back, what’s propelling us forward, who we are, and what we value) leads to the consolidation of memory - one of the key drivers of future performance.

Sources:

Swann, C., Schweickle, M. J., Peoples, G. E., Goddard, S. G., Stevens, C., & Vella, S. A. (2022). The potential benefits of nonspecific goals in physical activity promotion: Comparing open, do-your-best, and as-well-as-possible goals in a walking task. Journal of applied sport psychology, 34(2), 384-408

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American psychologist, 57(9), 705.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc.